Last month I took a road trip through an astonishing area known as the “The Outer Banks”— long, narrow, barrier islands off the coast of North Carolina. I was drawn to them by the works of Pat Conroy, a Southern novelist I admire, much of whose work is set thereabouts.

I was expecting these islands to be beautiful and culturally fascinating, but the experience was well beyond my expectations. Indeed, I found these islands utterly captivating— it makes me happy to think of them, and I long to return.

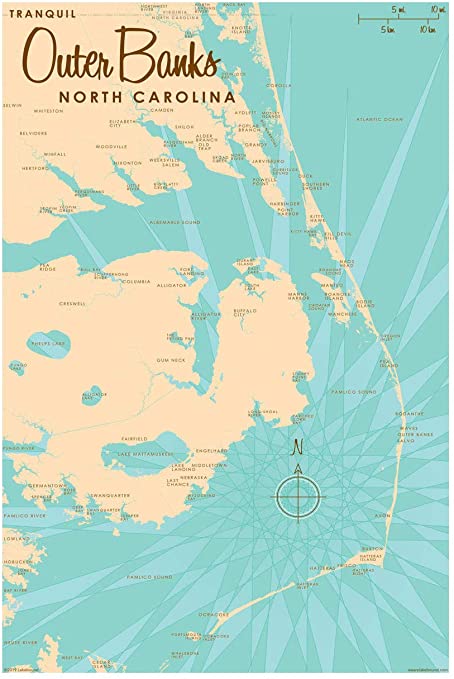

The Outer Banks (“OBX”) stretch some 320 km, north to south. I drove the whole thing during the week I was there, parts of it several times; it was constantly exhilarating— rather like sailing my wee rented Toyota over the windy, surfy sea itself. The weather was brilliant throughout; the whole experience was quite dream-like.

The settlements along these islands have fanciful names and layers of colonial and seafaring history— Currituck, Corolla, Kitty Hawk, Kill Devil Hills, Nag’s Head, Salvo, Buxton, Hatteras, Okracoke. Marine navigation here is exceptionally tricky; OBX is known as the Graveyard of the Atlantic; more than 5000 ships have come to grief there.

This area is best-known for the Wright Brothers’ first manned flight in 1903, at Kill Devil Hills. Less well-known are perhaps the details surrounding a pirate who operated in this area—the demonic genius, Edward Teach, professionally known as “Blackbeard”, who raised hell for years in these parts.

His luck eventually ran out, however: on a blustery November morning in 1718 authorities finally cornered him off Okracoke Island.They took no chances: they dispatched him by way of twenty bullets and five penetrating sword wounds. Moreover, he was decapitated in the process; his severed head was hoisted aloft by his grief-stricken shipmates. What loyal, sentimental guys they were!

There are a host of unlikely theories as to what happened to his skull—it may be in a museum in Massachusetts, it may have been converted to a punch-bowl, it may have been silvered and squirrelled away…you name it.

We’ll move on now. Over the next little while I’ll post a few photos to give you an idea of what a marvellous place this is— starting with my quirky motel, the venerable Sea Foam, in Nag’s Head. It’s a peculiar place—built in 1948 and, strange as it might seem, is on the US Register of Historic Places.

The motel itself is a real find. It is ancient, and certainly looks its age, but in a charming way. But it’s comfortable and clean, and its location— if you like sand dunes, surf, wind and sun— is perfect. At two feet of elevation, one does wonder about possible tsunamis and hurricanes, but after 74 years…well, let’s just say I was willing to chance it.

The manager, Lisa, was most obliging, and the off-season rate ($70/night) was a smoking deal. The neighbors were, as you might imagine, an eclectic, eccentric, jolly lot. The next room to mine was occupied by a 65 year- old Catholic/Hindu Vegan Irish/Canadian semi-retired physician. I couldn’t have made that up. We had lots to talk about.

I have a lifelong affinity for lighthouses. I grew up practically in the shadow of Canada’s most famous lighthouse, in Peggy’s Cove, Nova Scotia. I love them for the fact that their sole purpose for existing is heroic—to save human life. Who can tell what tragedy has been averted by a particular lighthouse on a certain perilous shore? Benjamin Franklin thought of a lighthouse as occupying the same spiritual space as a chapel. And he was a deist!

There are some stunningly beautiful lighthouses on the Outer Banks, within the area known as the Cape Hatteras National Seashore; the one on Bodie Island, just south of Nag’s Head is a joy to behold.

There was no one around when I visited except Frank, the National Park Service ranger, and a very pleasant and well-informed fellow he was. He seemed to have all the time in the world to chat with me. He told me he and his wife, Olivia, travel the country in their RV, working in various parks. They get their parking, utilities and groceries in exchange for their work guiding and caretaking the place. What a deal! Sounds like an interesting way to live; truly, I felt like signing up on the spot.

There is much to learn about this lighthouse; I’ll tell you several things I found interesting. It was built in 1872 and it’s 156’ tall.It’s the third lighthouse on this spot. It’s built in two layers, using normal, hand-laid bricks. The wall is 9’ thick at the base, 2’ at the top. The light is visible for 19 nautical miles.

For a fee you can climb it— if you can manage the 214 steps (there is a defibrillator, but sorry, no refunds). And the number of bricks? They say a million, but I doubt it was such a round number; the masons likely lost count. It looked like 10 million to me, and I could only see the outer layer!

The lens weighs 1.5 tonnes; it is an original “Fresnel”, designed by French physicist Augustin-Jean Fresnel (1788-1827), and superbly crafted by Barbier and Fenestre in Paris. Its main advantage is that it gives off a narrow, far-reaching beam. It is said that these lenses have saved a million ships, and who would doubt it?

But that’s enough for now. I bid a grateful farewell to Frank and Olivia, and climbed back into my stout Toyota. I was on my way to the storied Cape Hatteras next.

So, tootling south down route NC12 35 miles or so brings us into the neighborhood of Cape Hatteras, the easternmost part of the Outer Banks— and it’s a WAY out there. This is a very

exciting spot; freighted with much interesting history, mostly due to its extreme windward location and myriad hazards to navigation.

I don’t know about you, but when I hear “Cape Hatteras” my hair stands on end. I recall hearing, even from childhood, newscasts reporting a steady stream of calamity emanating from that aggressive jut of land. This Cape reminds me of a boxer who leads with his chin.

The excitement and calamity has much to do with hurricanes, with which I have a morbid fascination. I was interested to find that Cape Hatteras is, by far, the most frequent hurricane landfall in the country.

One after another they come—a major one every three years or so. After colliding with the Cape, they turn northward and tear up the Eastern Seaboard, finally taking a parting swipe at Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. The most recent hurricane to hit the Cape was Florence, in 2018— causing $24.2 billion in damage, and 54 deaths. The Cape must be on borrowed time by now.

Cape Hatteras is also the site of about a thousand shipwrecks—victims of the infamous Diamond Shoals, lying just offshore. The first vessel wrecked there was the English flagship Tiger in 1585; the latest was the scalloper Ocean Pursuit, in 2020. I noted with interest that a local writer called these waters “completely treacherous”. To my old sea-going ears, that phrase has a thrilling ring.

Diamond Shoals are constantly shifting sand bars upon which a hapless ship may easily run aground and get battered to pieces by the surf. A mariner’s eyes can play tricks on him here; it is often hard to tell the land from the sea— until it’s too late. One’s heart itself sinks at the thought.

All that aside, the day I visited in April the whole place seemed utterly benign— heavenly, really—sunny and warm, with an onshore breeze that seemed to caress the brow of this lonesome sailor. The centrepiece of the Cape Hatteras experience is, of course, its lighthouse— similar but bigger than the one on Bodie Island.

After it was erected in1840, the number of shipwrecks quickly declined. At 193’ feet, it is the tallest brick lighthouse in the world; its light is clear thirty miles out to sea. It’s utterly magnificent to behold— an enormous white tapered tower with a distinctive black spiral. It put me in mind of a stone god; I can imagine seafarers bowing down in adoration before it.

Perhaps the most astonishing fact about this place is this: the lighthouse itself had to be rescued from the sea. By 1999 the ocean was creeping ever-closer to its foundation and bold remediation had to be undertaken. The National Academy of Sciences was asked to advise local authorities on how to move this 4830 ton treasure to safety more than half a mile inland.

The companies involved had charming names—the International Chimney Corporation of Buffalo, N.Y., and Expert House Movers of Sharptown, MD. These guys were the top guns in their fields; they used a combination of jacks, rollers and tracks — and, no doubt, “blood, tears, toil and sweat” — and they did a superlative job.

If you go— and you must — don’t miss the lovely Museum of the Sea on the same site. It’s filled with local lore, including artefacts from the dreaded German submarine, U-701, sunk by the USAAF in July, 1942, after it had sent nine Allied ships to the bottom.

But it’s time to shove off south again, to our last stop along the Outer Banks— the distinctive and remote Ocracoke Island.

Okracoke Island has an intriguing nature; the word unique springs to mind— meaning alone in the universe. If you drive from north to south along the Hatteras National Seashore it’s your last stop, the last major island in the chain. And it takes some doing to get there.

By that I mean you have to take a ferry. That doesn’t sound like much, but I turned up one afternoon expecting to drive right on— and was told I was out of luck; the only remaining sailing for that day was “full.” Oddly enough, they don’t do reservations — so it’s first-come-first-served, which creates a perpetual pandemonium, everyone competing for a spot on the tiny vessel.

Indeed, when I arrived there was a big jumble of cars, trucks, motorcycles, bicycles, foot-passengers and likely a dog-cart or two. I soon learned that the ferry only holds thirty or so vehicles. The security man advised that I had better arrive by 5 AM the next day to be sure to get aboard. What?

So I had to head back to the Sea Foam (65 miles), and angle for another night’s accommodation. I set my alarm for 3AM, and grabbed 4 hours of sleep. It’s actually quite fun awakening at three in the morning and not knowing where on earth you will be spending the next night. This is my idea of a good time.

In twenty minutes I had said goodbye to the dear old Sea Foam and set out; my little Corolla purred along eagerly. At that hour many deer were out and about– scattered willy-nilly along NC12. I picked my way carefully to the ferry dock at the south end of Hatteras Island. At 5:30 I rolled onto the tiny ferry with the big name: Chicamacomico. Dawn was breaking. It was terrific to be there, launching into the unknown.

The ferry does not just zip right across the two-mile- wide Hatteras Inlet between the two islands. Because of the shifting, sandy bottom and extreme shallowness (~6’), the ferry must swing miles out to the east into Pamlico Sound in order to avoid grounding. The trip actually takes about an hour; its course is wonderfully meandering. I’d estimate it covers 20 nautical miles before making landfall. And, wonder of wonders— it’s free. I don’t think the Okracokers want a causeway. And if you ask me, things are great the way they are.

The ferry does not just zip right across the two-mile- wide Hatteras Inlet between the two islands. Because of the shifting, sandy bottom and extreme shallowness (~6’), the ferry must swing miles out to the east into Pamlico Sound in order to avoid grounding. The trip actually takes about an hour; its course is wonderfully meandering. I’d estimate it covers 20 nautical miles before making landfall. And, wonder of wonders— it’s free. I don’t think the Okracokers want a causeway. And if you ask me, things are great the way they are.

Of course I was starving when I got there, and went straight to the well-reviewed Pony Island Restaurant in Okracoke village, 12 miles south of the ferry dock, known as “Okracoke Island’s oldest eatery.” It’s a cozy, relaxed sort of place, and I was happy to be there.

Most of the customers were watermen. They spoke of weather, boats, tides, wind, the price of tuna, drum, mahi and sailfish. Their forefathers could have had the same conversation generations ago. The fishing here is legendary.

I ordered the “Big Pony Breakfast”. I wolfed it down in no time, and it was just the ticket. I let out my belt. Only later did I wonder (given the abundance of wild horses on Okracoke) if my breakfast might have had any equine ingredients. If there were, I can’t say I wasn’t warned. Horse or not, the whole thing was yummy, and quite fortifying.

The many things of interest are well-described on Wikitravel and the island’s websites. Note that 16 mile-long Okracoke Beach has been named the best in the nation for 2022. And the lighthouse is a real corker.

For my two cents, I’ll mention the one thing I found most touching; it’s the British Cemetery in the village. On a random walk around town you can’t miss it; I was the only person there that morning. How, I asked myself, did it come to be here?

This tiny but impressive cemetery was established as a result of a tragedy that occurred May 11, 1942. A converted British trawler named the HMT Bedfordshire was torpedoed by U-558 while assisting the U.S. Navy with anti-submarine patrols off Okracoke. Her crew of 36 was composed of British and Canadian sailors; all hands were lost. I can see the whole miserable scene playing out in my mind’s eye; strangely enough, it’s in black-and-white.

Four bodies from the Bedfordshire washed ashore over the next few days; two were identified. Each was identified and given a proper burial in this dedicated plot. The land is permanently leased to the British Government, and an annual ceremony is held here each May 11, attended by representatives of the British Navy, the U.S.Coast Guard, and the National Park Service.

A British Navy White Ensign flies bravely over the graves. Like I say, I get choked-up when I think of it. Perhaps it’s because my Dad was a naval officer.

And so, my friends, that pretty well does it for my visit to the Outer Banks. I feel a glow in my heart when I recall the things I learned there; I long to return.

Later that day I took another ferry south….to Cedar Island, and beyond.

Toot-toot!

Facebook Comments