One of the gladdest moments in human life, methinks, is the departure upon a distant journey to unknown lands.”

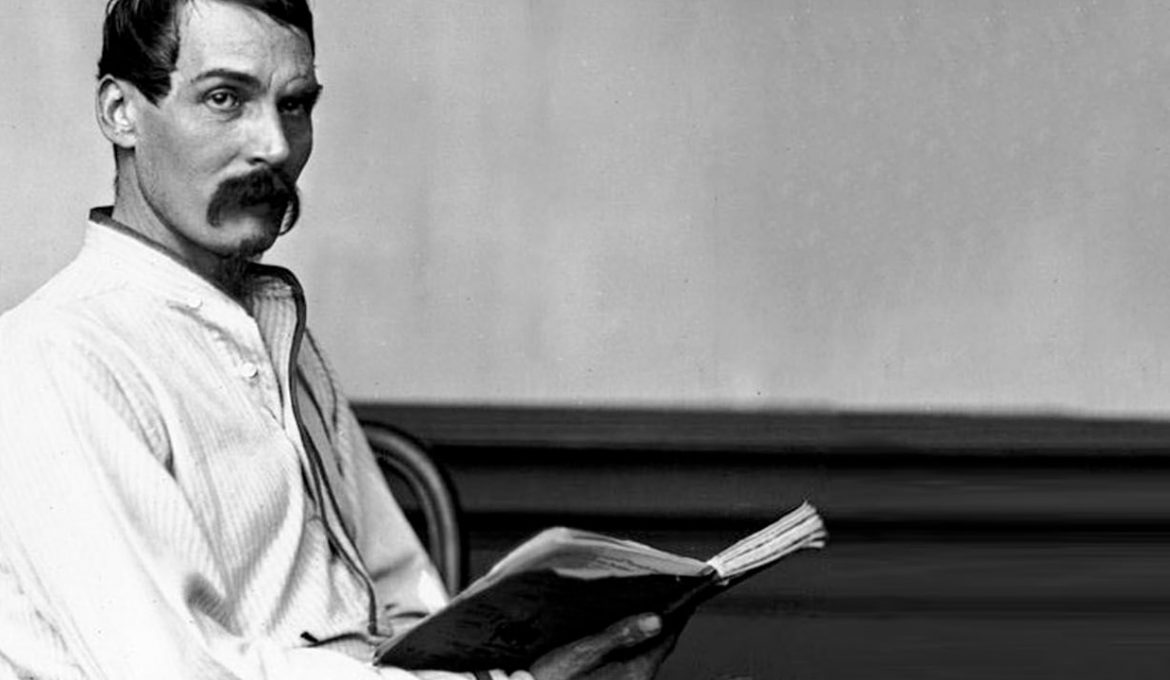

Sir Richard Burton

When I was nine I was given an assignment to write an essay on what I planned to do when I grew up. I was to read the fruits of my labour to my Grade 4 class the following week.

Well, I rather panicked, trying to come up with a topic that would be both impressive and plausible. I wracked my little brain for days, but nothing much was coming. After all that thinking, I fell into a fugue of agonizing procrastination. What on earth should I do?

With only one day to go, I sat on my bed, pencil in hand, sobbing. Tears splashed down on the blank page before me. Just then, my father happened to walk by my door. “What’s wrong, boy?” he asked. After I explained my predicament, he smiled and said, “Oh, that’s easy….. tell them you’re going to be an explorer.”

Right-o, thought I— that’s it— an explorer! I then proceeded to imagine myself as a grown-up, moving smoothly around the world—solving mysteries, mastering languages, correcting maps, leading expeditions and so on. I fancied I might even venture into regions noted on ancient maps as Here Be Dragons. So I dashed off a few paragraphs to that effect.

My essay was warmly received by my teacher, the perceptive Miss Power, and all but a single contrarian classmate. The experience was formative for me; from that moment I was captivated by the idea of exploring the world, having adventures, and surviving to tell the story. I give old Dad the credit.

I think it would be interesting for us to study the lives of certain famous explorers — not just their exploits, but also to discover what sort of person becomes one. What of their personal and family lives? What are the sacrifices and rewards of being an explorer? Who funds these adventures?

So, be my companion as we look into the lives of selected renowned explorers. We’ll start with a great favourite of mine, the brilliant Englishman Sir Richard Francis Burton, KCMG, FRGS. He’s been described as the “Victorian Indiana Jones.” He’s also been called a maverick and an anti-hero; his critics called him “Ruffian Dick”, a rather gentlemanly Victorian insult.

I believe Burton was uniquely gifted. In addition to being an fearless explorer, he was a prolific author on a huge array of subjects—from falconry, to fencing, to eastern erotic practices. He was a linguistic wizard— fluent in dozens of languages. He was, at various times, also a spy, a poet, a soldier, a diplomat and— a “ladies man.”

He was born in 1821 in Torquay, Devon. His father was an army officer, his mother an heiress of note. His youth was spent there, and in Italy and France, where he picked up several languages. He was described as a “gypsy-eyed” boy noted for “raising hell” while travelling with his family. He never related well to authority. One imagines he was a handful.

Burton entered Trinity College, Oxford, at the age of nineteen. He and Oxford were evidently a poor fit. Despite his remarkable intelligence and ability, his free-wheeling style tended to provoke both his superiors and his peers. On one occasion, a classmate mocked his huge moustache, and Burton promptly challenged him to a duel. The classmate made a run for it.

In 1842 he attended a “steeplechase”— a cross-country horse race— a serious infraction of college rules. He thought he’d escape with a stern warning, but to his great surprise he was swiftly expelled from Oxford, without benefit of degree. Thus liberated from dreary college life, as he saw it, he went to India and joined the army of the British East India Company. His life had taken a decidedly intriguing turn.

Take, for instance, his idea of going to Mecca. Astonishing as it seems, till then this had never been done by any European. Any infidel caught doing so was likely to be speedily executed on charges of blasphemy. When asked why he wanted to do it, he implied he considered himself invincible, and wanted to prove it to everyone. Danger for him was an irresistible stimulant. Without it, he’d likely have died from boredom—in his view, a poor way to die, indeed.

He approached the venerable Royal Geographic Society for funding for this lunatic endeavour. He must have had a silver tongue, because they agreed, but with conditions. The Society wisely insisted Burton return alive, with scholarly report in hand, before any payment would be made.

Here’s how he did it. Every Muslim is expected to take the Haj— the pilgrimage to Mecca— so he decided to impersonate a pilgrim himself. His dark hair and complexion helped. He studied Islamic customs in Egypt for four years— ways of eating, drinking, sleeping and praying. His assumed identity was “Mohammed”— a wandering Sufi mystic of mixed Afghan-Indian-Burmese background— a holy man, not subject to interrogation. He carried a hollowed-out Quran containing a compass, a watch, cash and writing material; he also concealed a pistol. To add authenticity, he went so far as to have himself circumcised.

Thus disguised, he joined a caravan crossing “the Empty Quarter” of the Arabian peninsula, the world’s largest sand desert—a blank space on his map. The 11-month the trek was brutal, but on Sept 11, 1853, Burton slipped into Mecca. He went directly to the Great Mosque—the largest such building in the world. In the middle of it he encountered a black granite cuboid building, the mysterious Ka’aba. To Muslims, this is the holiest site in the world, the very “House of Allah.”

In his role as a pilgrim, Burton performed the tawaf, a counterclockwise walk seven times around the Ka’aba. He kissed the Black Stone in the Ka’aba’s eastern corner. During his time in Mecca, Burton never broke character. In fact, he was so convincing that he gained entry to the hallowed Ka’aba itself, where, pretending to pray, he coolly took a pencil stub and sketched the floor plan on a fold of his robe. To say he had nerves of steel is an understatement.

In due course he made his way back to England. The Royal Geographic Society was well-satisfied; Burton produced what turned out to be a best-selling book— A Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to Al-Madina and Meccah. Fame and wealth followed its publication and it has since become a classic of travel literature. It is a great pleasure to read— I found it fascinating and often amusing.

Burton’s subsequent life was one exploit after another. Amazingly, he died of natural causes in at the age of 69. His undertaker remarked that his bodily scars told the story of his life of endless curiosity. He is buried with his wife, Isabel, in a tomb shaped like a Bedouin tent, at St.Mary Magdalen Catholic Church, Mortlake, SW London. I visited their grave not long ago.

A line he wrote pretty much sums the man up: “One of the gladdest moments in human life, methinks, is the departure upon a distant journey to unknown lands.”

Just so. I’d loved to have known him.

Facebook Comments