When I was young I thought traveling by air was the most amazing thing conceivable. I remember flying from Halifax to St. John’s in a Trans-Canada Airlines Canadair North Star. The four prop-engines nearly deafened me, but it was great fun the whole way. I thought the stewardesses were terrific: rather like militarized angles, gliding the aisle – smiling and nodding – attending to every need.

Nowadays, however, one never – but never – hears grown-ups say they enjoyed a flight. People complain about inconvenient departures, baggage fees, cramped seats, indifferent service, stale air, a coughing seatmate, paying good money for bad food, and so on. We’re truly jaded.

Personally, I’d rather take the Greyhound.

High on the list of air-travel irritants is having to endure security screening. I was travelling with my wheel-chair-bound 86 year-old mother a few years ago; naturally, she had to pass through the security gauntlet: metal detector, pat-down, search of purse, shoes, pockets, hat and carry-on. After much diligence, the officers did come up with something they found suspicious: a pair of nail scissors (gasp!) with inch-long blades. Apart from their utility, these scissors were of sentimental value – part of a set – a gift from her late husband. In the name of airline safety, they were confiscated on the spot. She started to cry. The whole scene struck me as brainless – and heartless.

How did we get to the place where such rote precautions are considered sensible? Is there a smarter way of identifying villains trying to board a plane? Who in the world is best at this, and why aren’t most airports in the world doing it that way?

Routine security screening – physical search – started in the US in 1973, after the hijacking of a Southern Airways Douglas DC-9 over Birmingham Alabama. The hijackers boarded the plane with handguns and grenades (imagine!); they threatened to crash the plane into a nuclear power plant. They changed their minds and flew to Cuba. Good call.

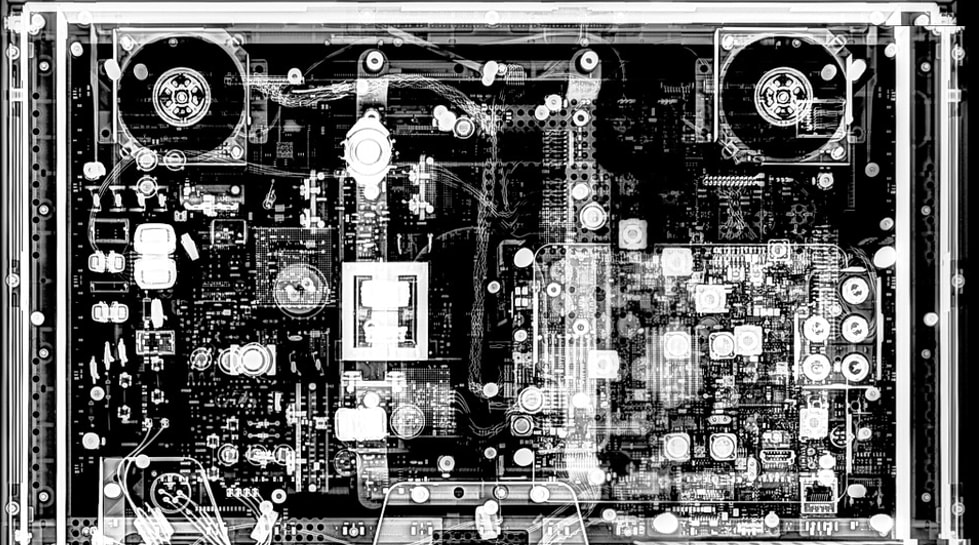

Through the following years many measures have been adopted to improve security: metal detectors, x-rays, full-body scanners, explosive detection techniques, sniffer-dogs and so on. These measures seem reasonably effective, but are terribly inefficient, inconvenient and costly. Incidentally the budget of the US Department of Homeland Security is over $41B this year alone.

So, I did some checking to see which airports have the best reputation for security. The trick, of course, is to be effective, efficient and courteous – all at the same time. I was not surprised to learn that Ben Gurion International Airport (LLBG) in Tel Aviv, Israel is tops. It is fondly known as “Natbag”. No flight from there has ever been hijacked, and there hasn’t been a terrorist attack there since 1972, when three members the Japanese Red Army machine-gunned a hundred people, killing 26. Yuck.

I’ve been to Natbag a number of times, and I must say, it is in a class of its own. If you’re on the level, rest assured, all will be well.

But if you’re planning any monkey-business, agents will, metaphorically speaking, stuff you in a sack and take you somewhere unpleasant for ‘enhanced’ interrogation. This will last at least as long as it takes to miss your flight.

So, what measures does Ben Gution Airport take to achieve its top ranking? Basically, rather than relying on technological screening, staff engages in what’s termed “personal interaction” – putting each prospective passenger through a number of personal evaluations. In fact, every potential passenger, as a matter of policy, is considered a terrorist until proved otherwise.

It starts before the passenger even gets to the airport. When a person books a flight involving LLBG, his name is checked against a list of terrorist suspects compiled by law-enforcement agencies – Interpol, the FBI and the Israeli Intelligence Service, Shin Bet.

Screening continues at the main gate where each incoming driver, passenger and vehicle is inspected by soldiers armed with Uzis. Each person is identified, the vehicle is weighed, the trunk x-rayed and the undercarriage inspected with mirrors. Any suspicious person or vehicle is further scrutinized.

If he makes it to the terminal, each passenger is interviewed by highly-trained agents. They look for anything suspicious – apparent anxiety, sweatiness, poor eye contact, no good reason for being in Israel, a dubious travel history – anything that triggers a certain “gut reaction” in the interviewer.

There are many other security techniques at LLBG, but notably, you don’t have to remove your shoes as you do in most North American airports. If you’ve ever wondered why this is, it goes back to December 22, 2001 – just three months after “9/11”. The world was a nervous wreck.

On that day British Islamic extremist Richard Reid boarded a flight from Paris to Miami. His aim was to blow up his plane with explosives concealed in the heels of his hiking boots. In midflight, he tried to light the fuses (hidden in the laces), but passengers smelled the match and raised the alarm, and Reid – all 6’4, 220 pounds of him – was overpowered and bound with belts and headset cords. The plane landed safely in Boston.

Amazingly, the fuses failed to ignite because they had become wet. The reason? There’d been a strike at Paris Orly Airport at the time, and Reid had to stand on the tarmac before boarding; it was raining!

Where’s he now? Reid is serving the first of three life-sentences plus 110 years at Florence Supermax Penitentiary in Colorado. (Does this type of judicial sentence make any sense?)

Isaac Yeffet, former head of security at LLBG, said if Reid had come through Tel Aviv, he would have never been allowed to board. Yeffet cited several eyebrow-raising anomalies: Reid paid $3000 cash for a one-way ticket; he had no job, but often travelled to Afghanistan; he was a Muslim convert with fishy connections; he had no luggage and had a long UK criminal record. Incredibly, security in Paris had turned him away the day before, but allowed him to fly next day. What??!

“What did we learn from this?” Yeffet asks. “Just to tell the passenger from now on, you take off your shoes when you come to the airport? This I call a patch on top of a patch…stop relying only on technology…technology can help the qualified, well-trained human being but cannot replace him.”

Could we be doing security more effectively in North America? Undoubtedly, a resounding yes! It’s not that hard. I rest my case.

Facebook Comments